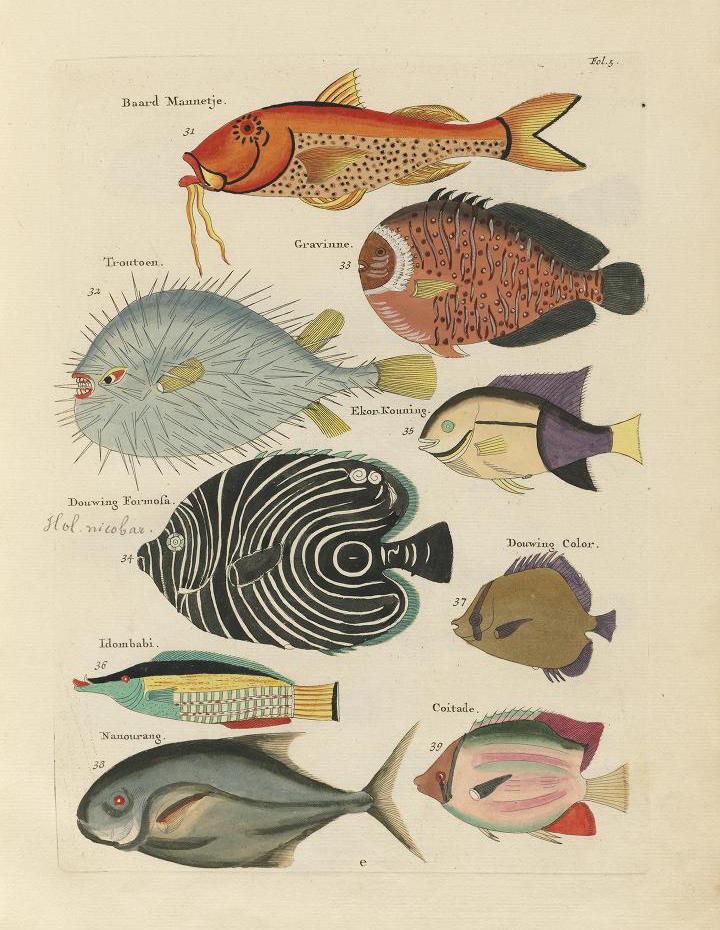

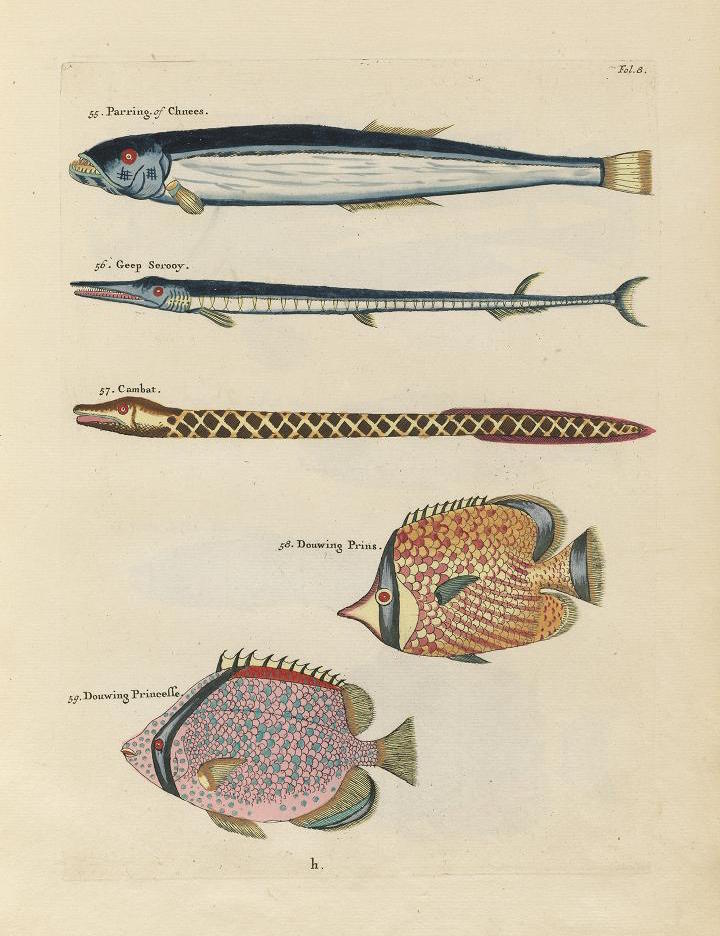

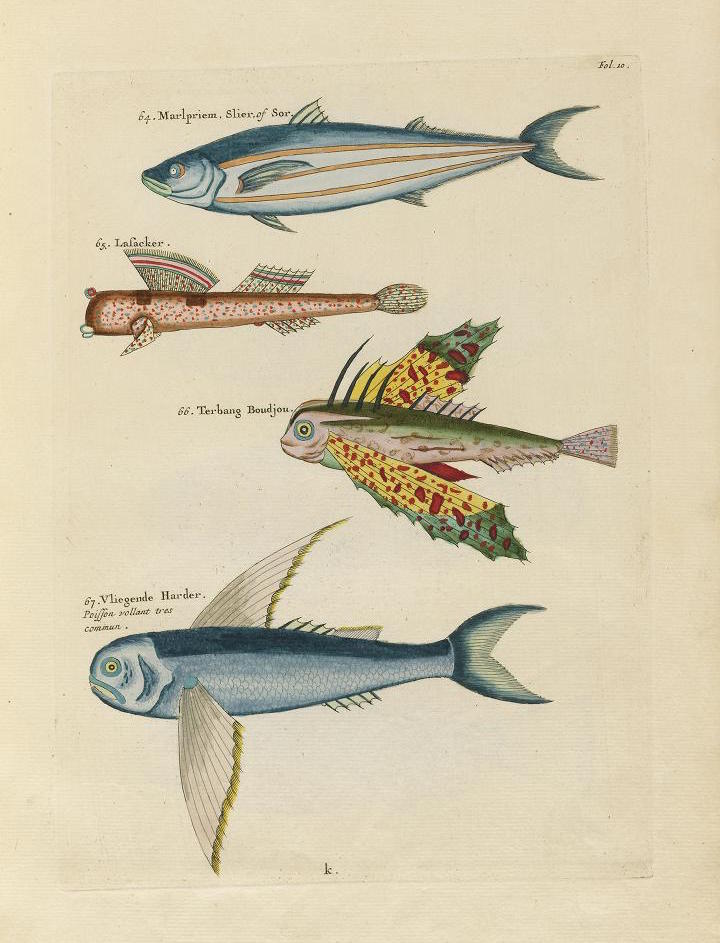

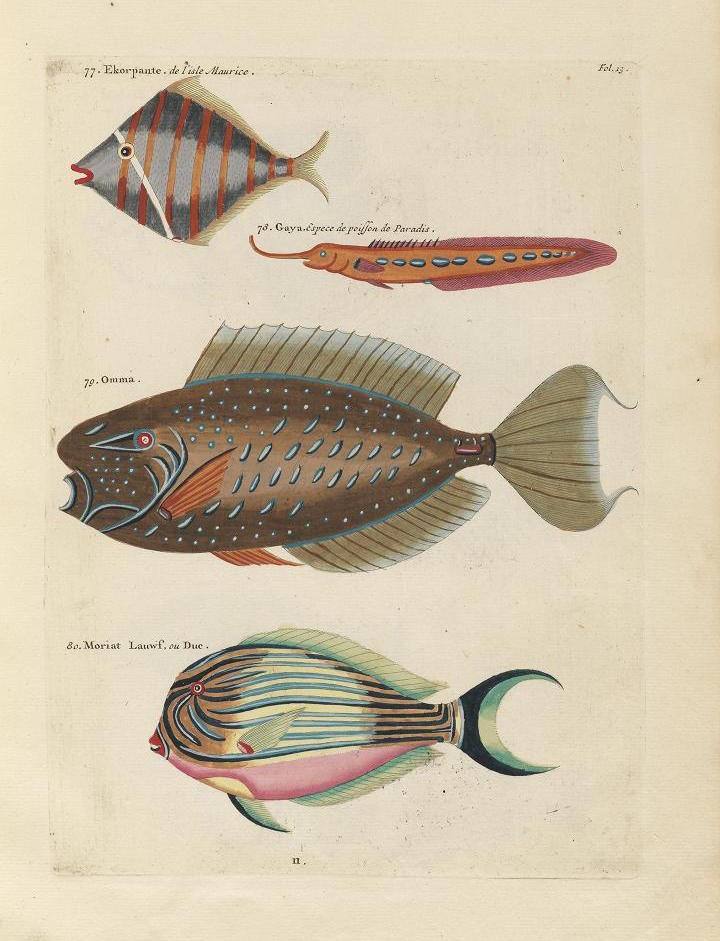

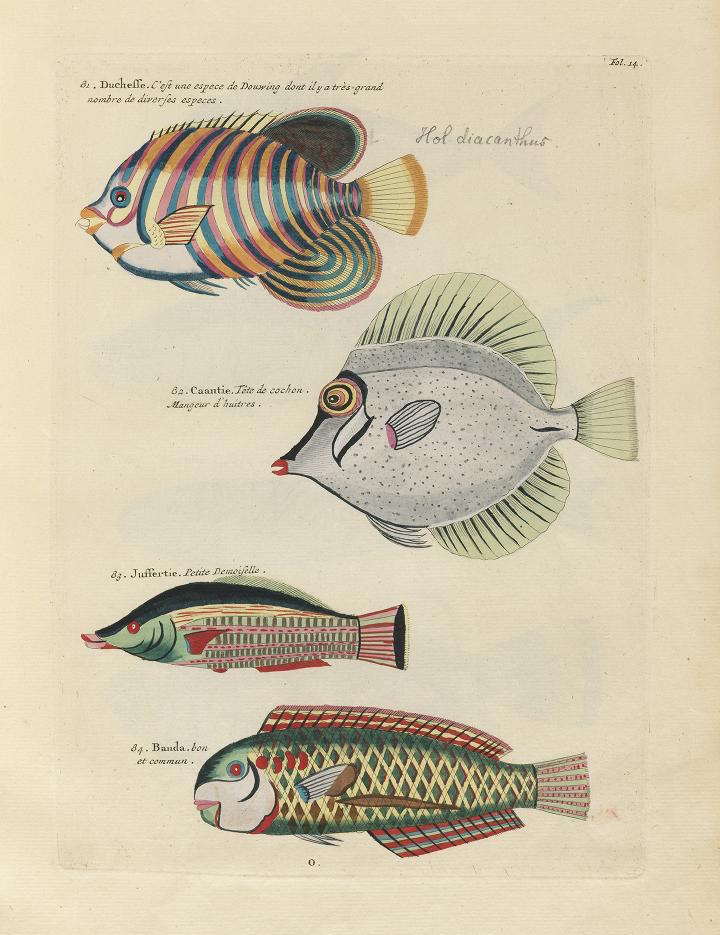

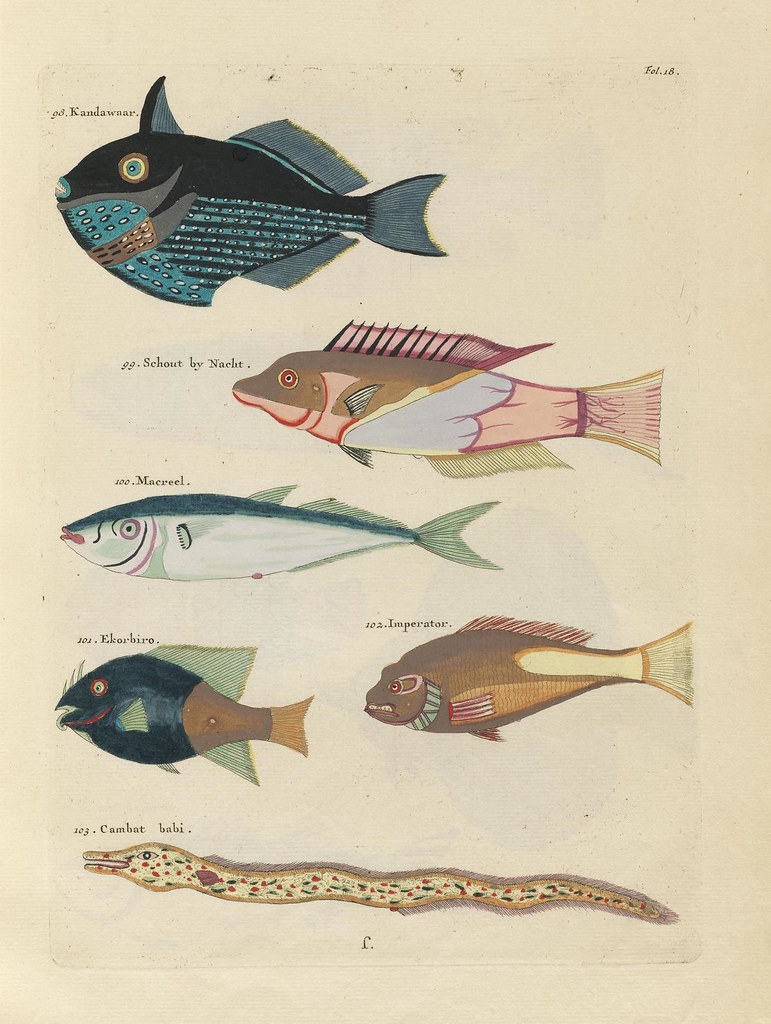

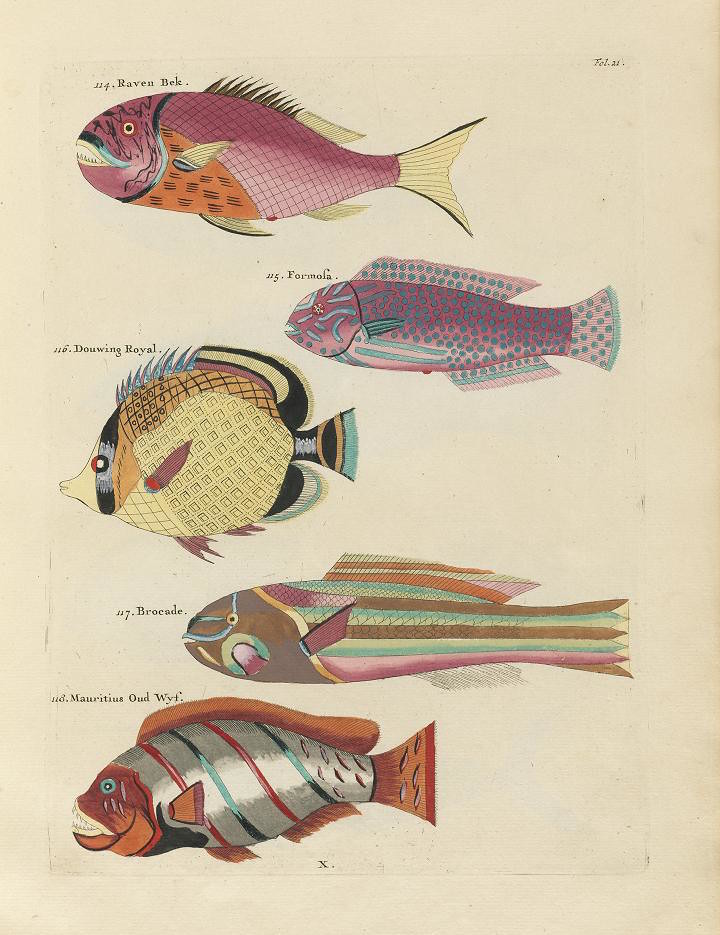

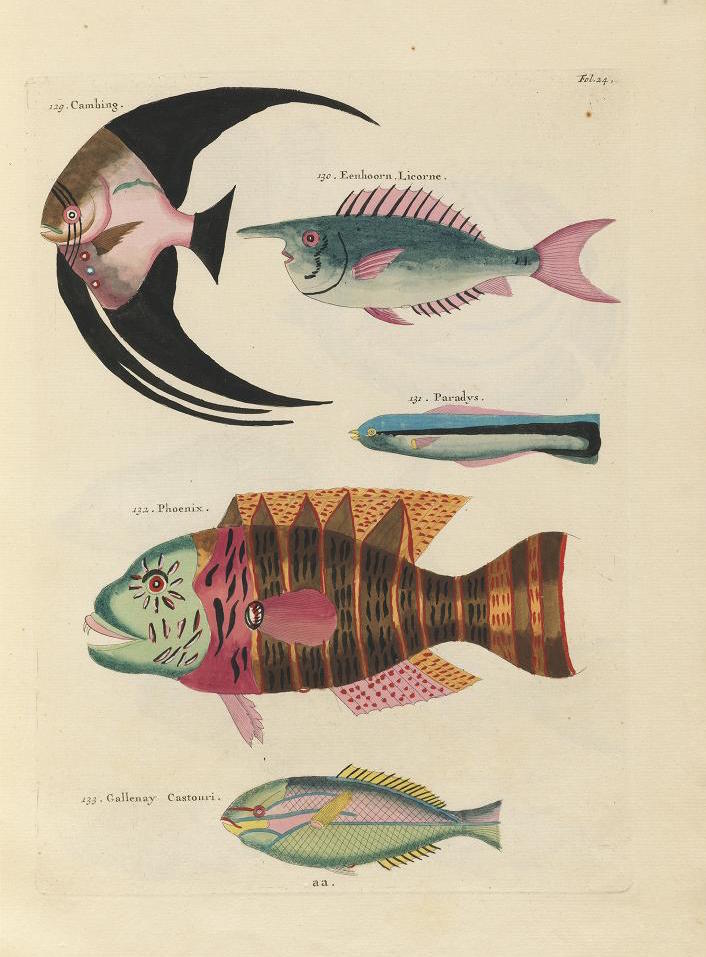

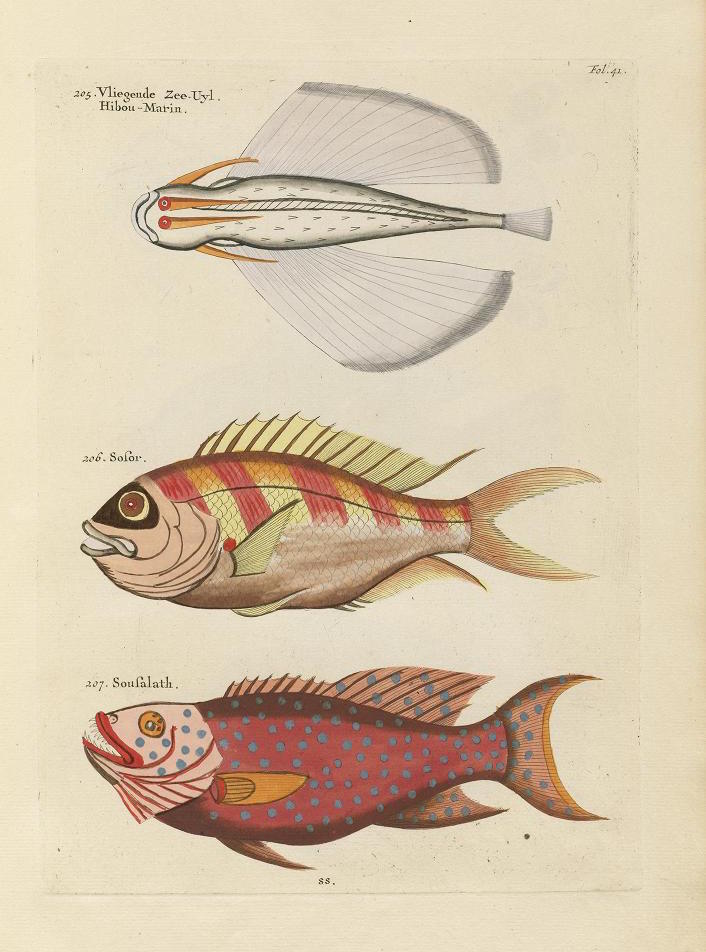

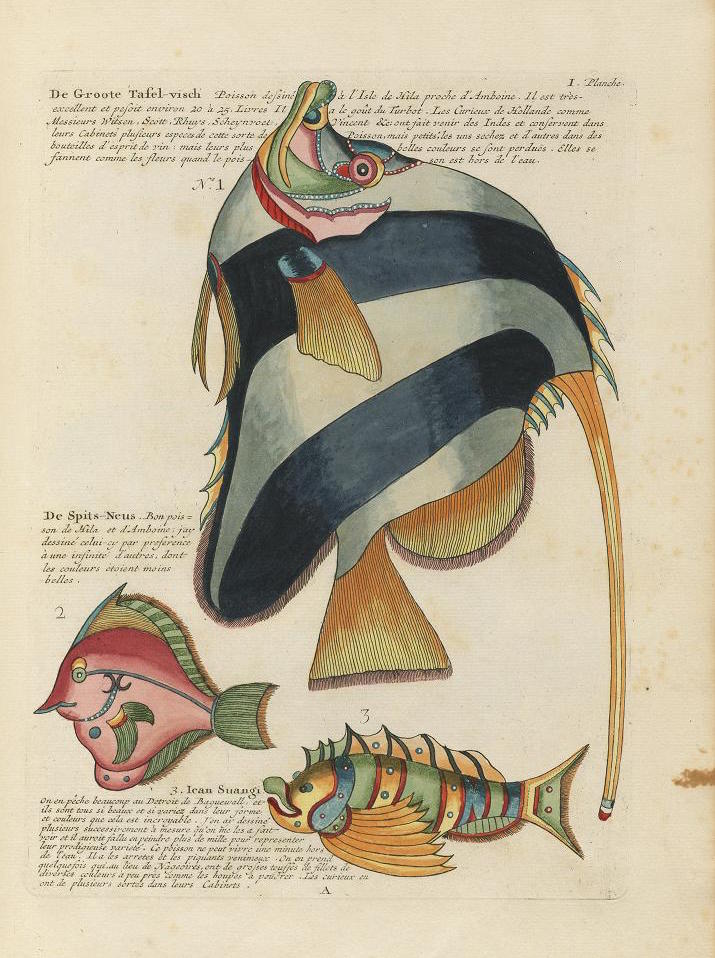

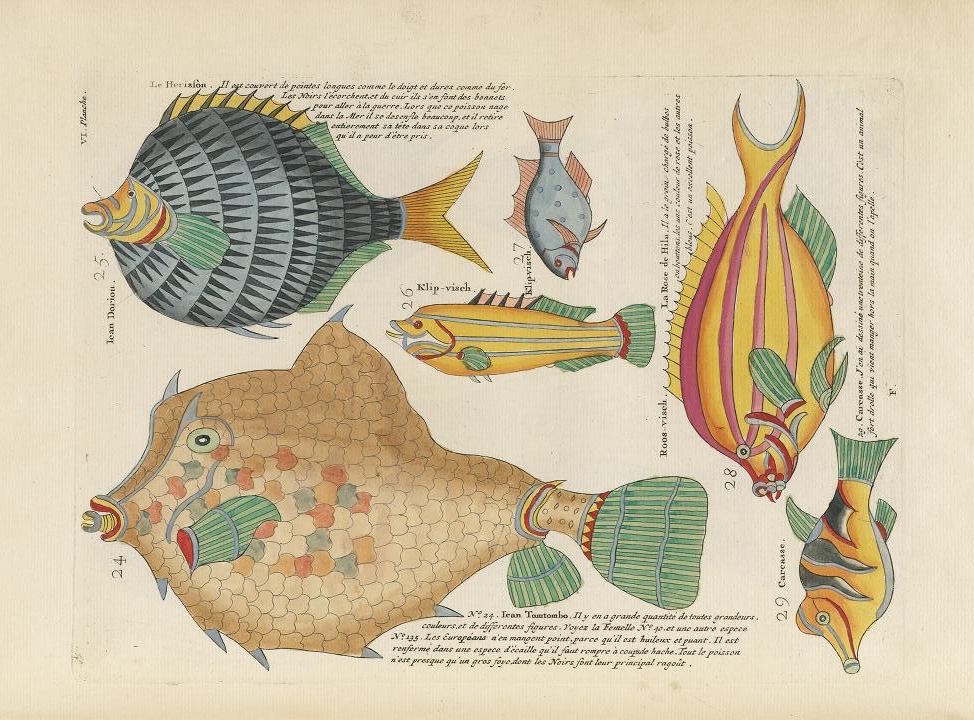

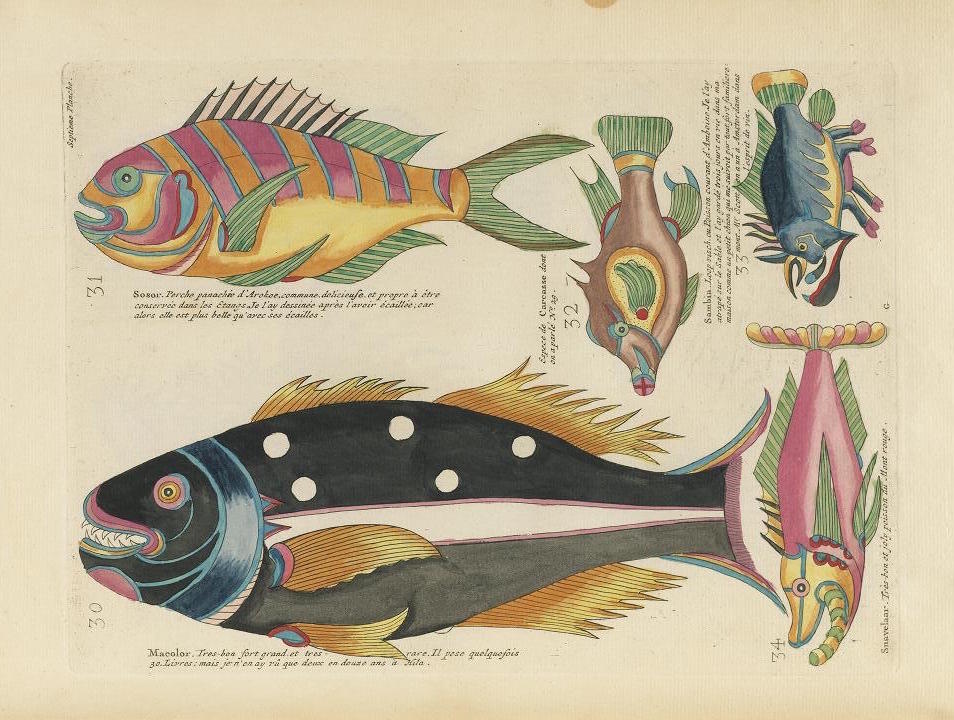

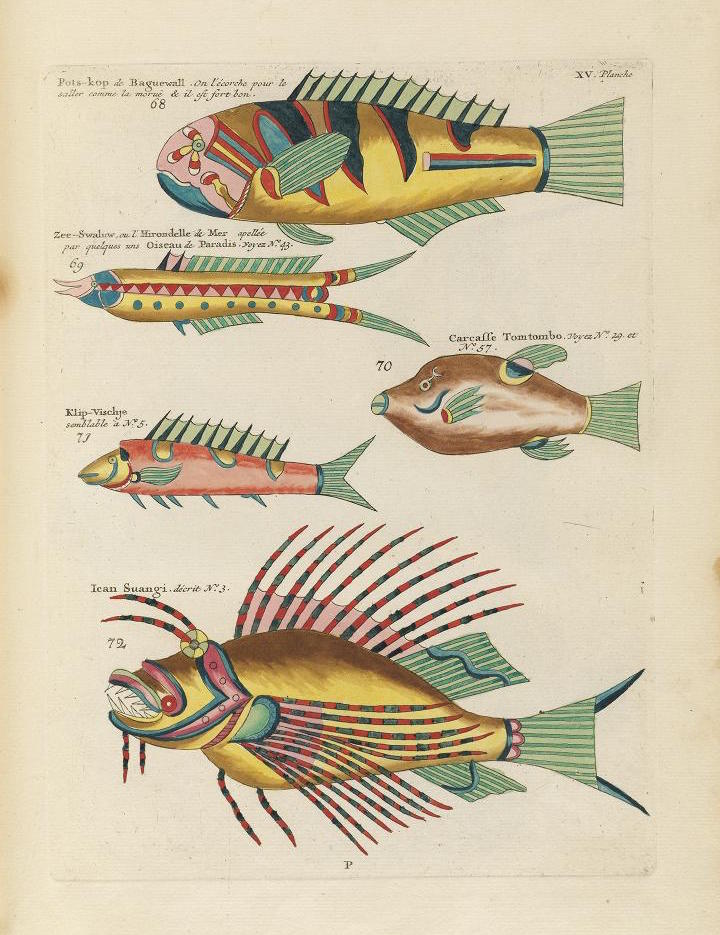

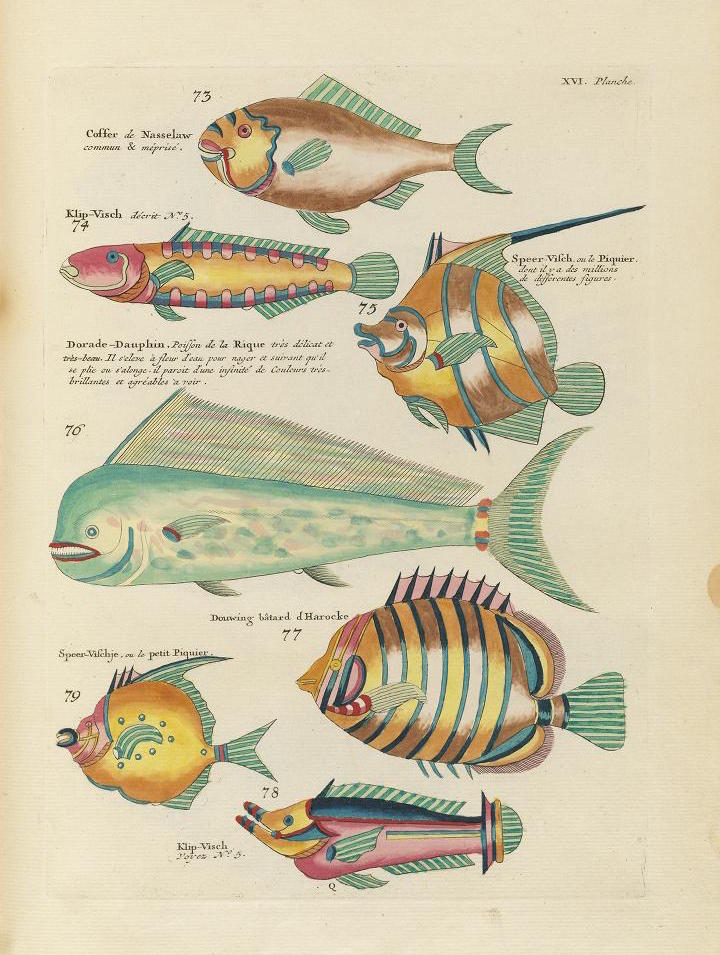

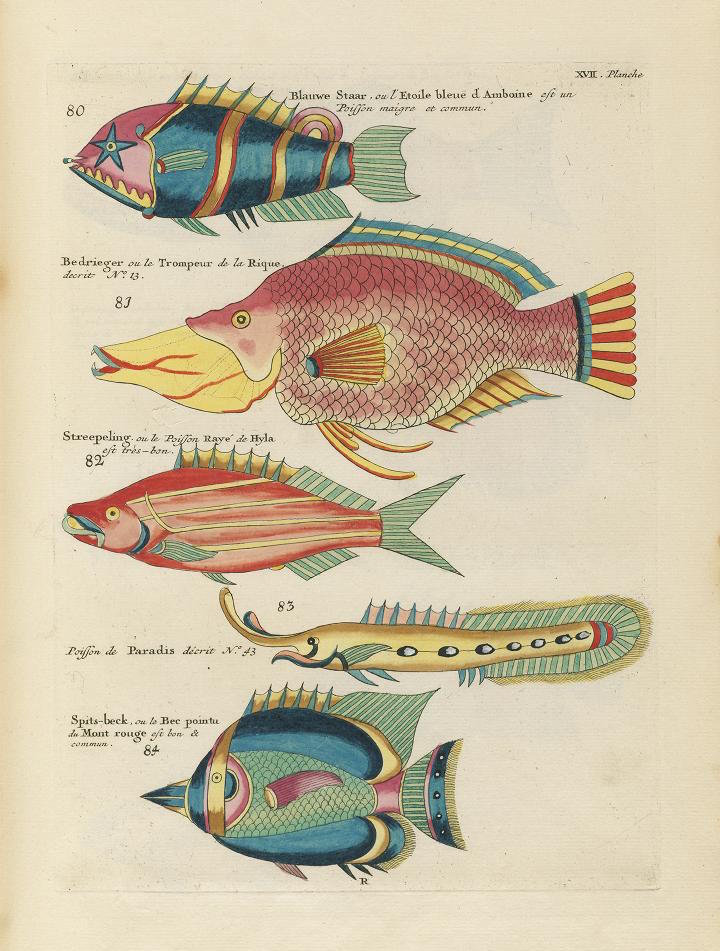

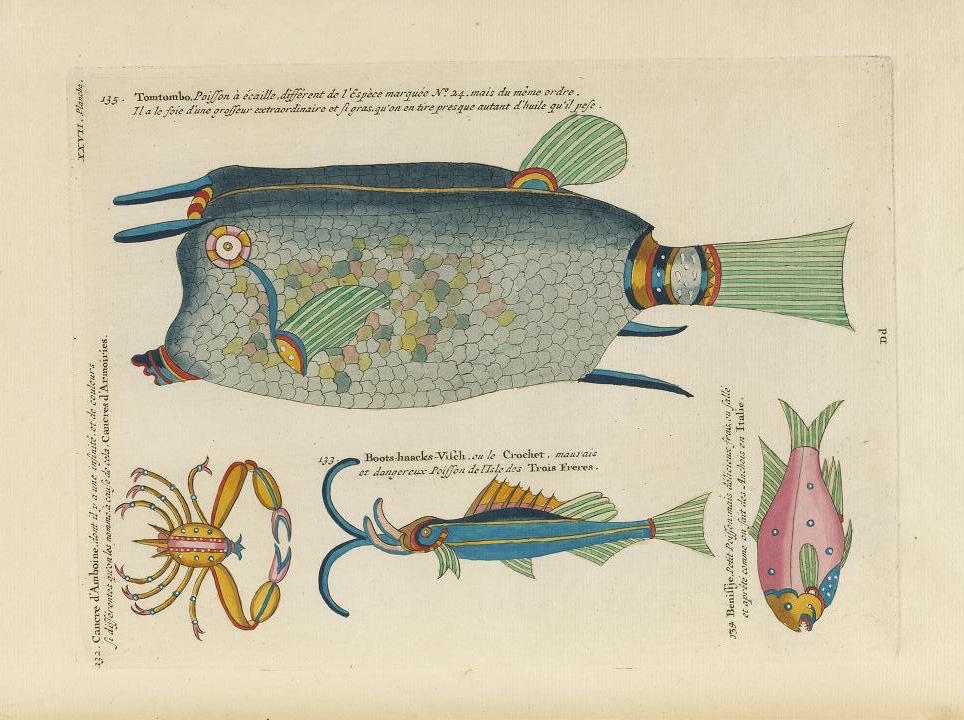

Images from the First Colour Publication on Fish (1754)

Originally published in 1719, with a second edition in 1754, Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes can lay claim to being the earliest known publication in colour on fish — in this case, celebrating those hailing from the waters of the East Indies. This wonderful book is the creation of Louis Renard — a publisher, bookseller, and spy for the British Crown (employed by Queen Anne, George I and George II). This latter role, which saw him help guarantee the Protestant succession to the throne by denying James Stuart supplies, was not particularly secret and it seems Renard used the fact to add some intrigue to his books. This work, for example, is actually dedicated to George I, and the title-page describes the publisher as “Louis Renard, Agent de Sa Majesté Britannique”.

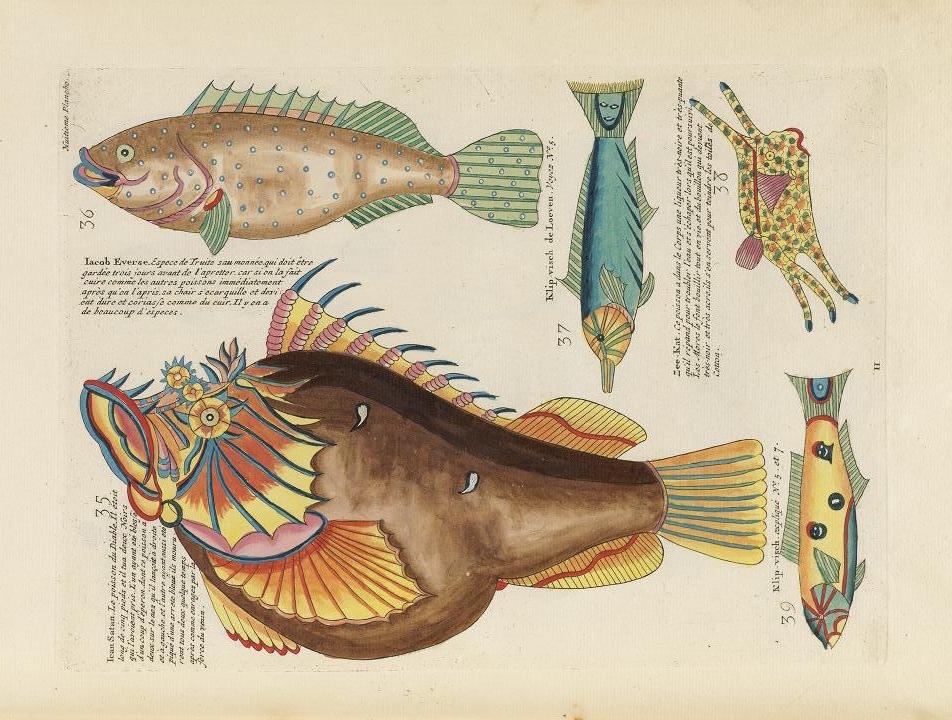

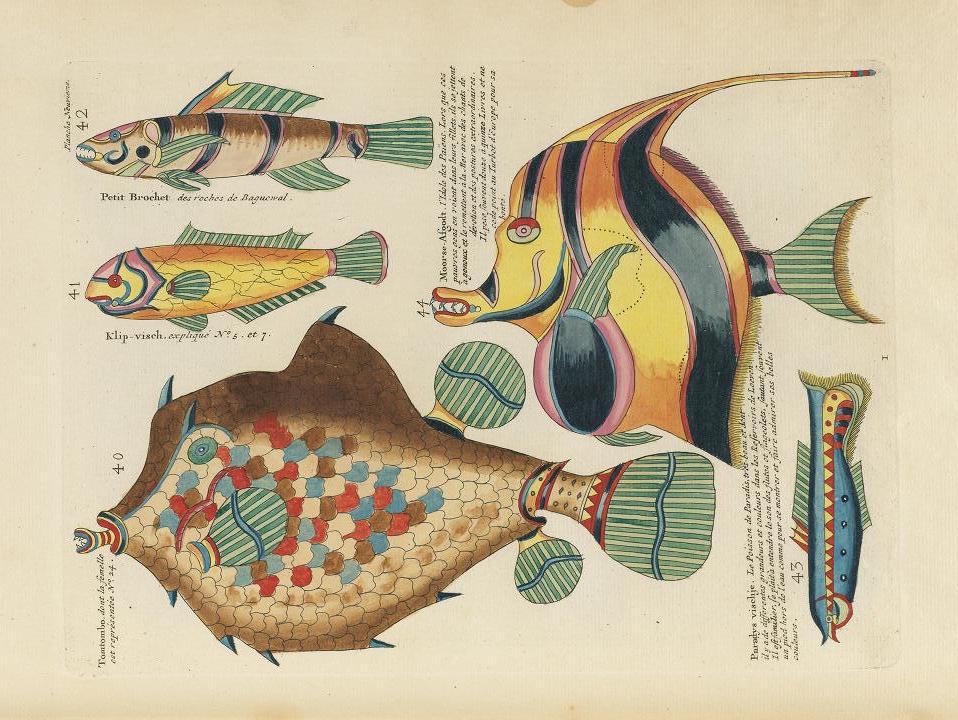

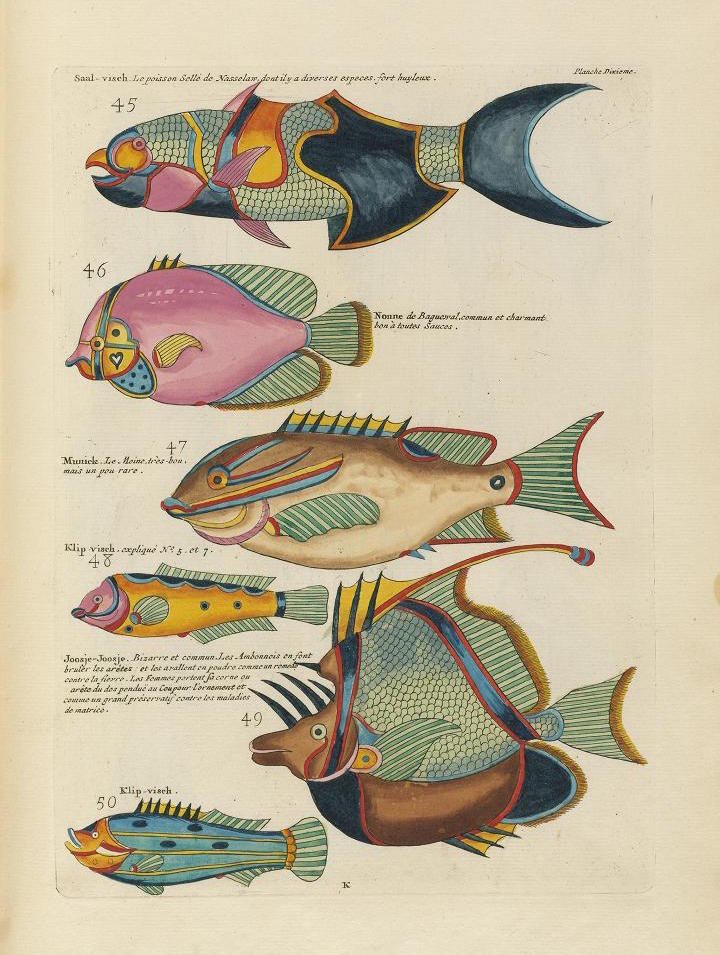

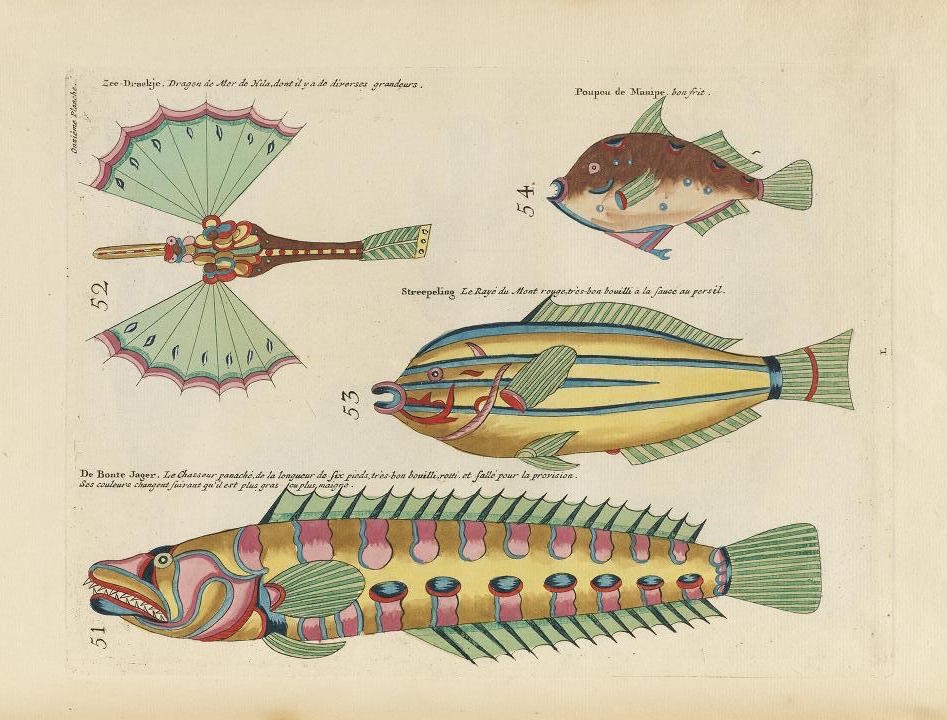

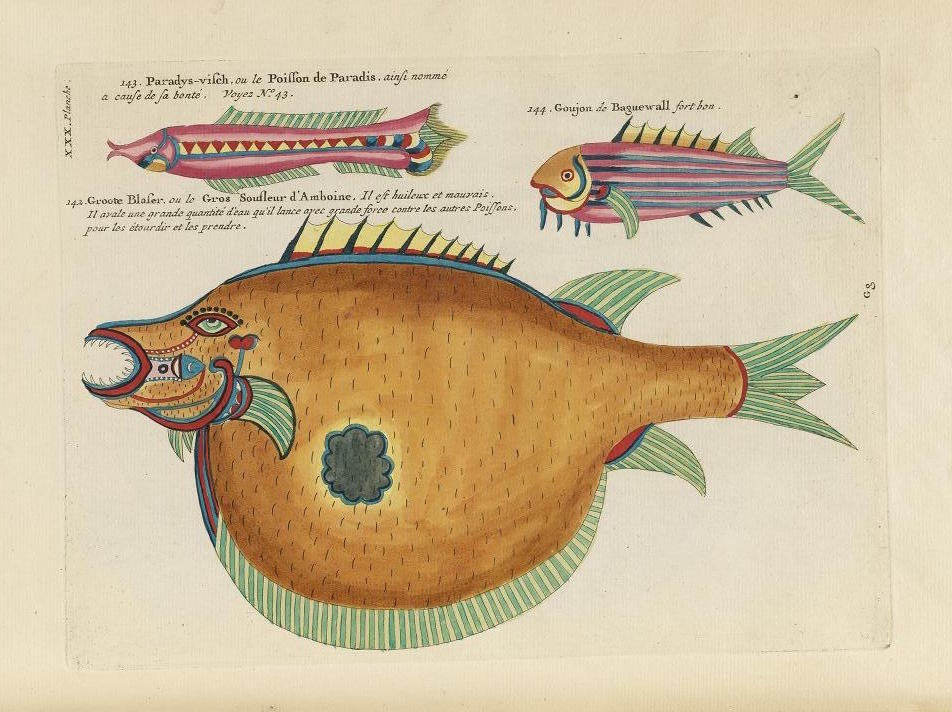

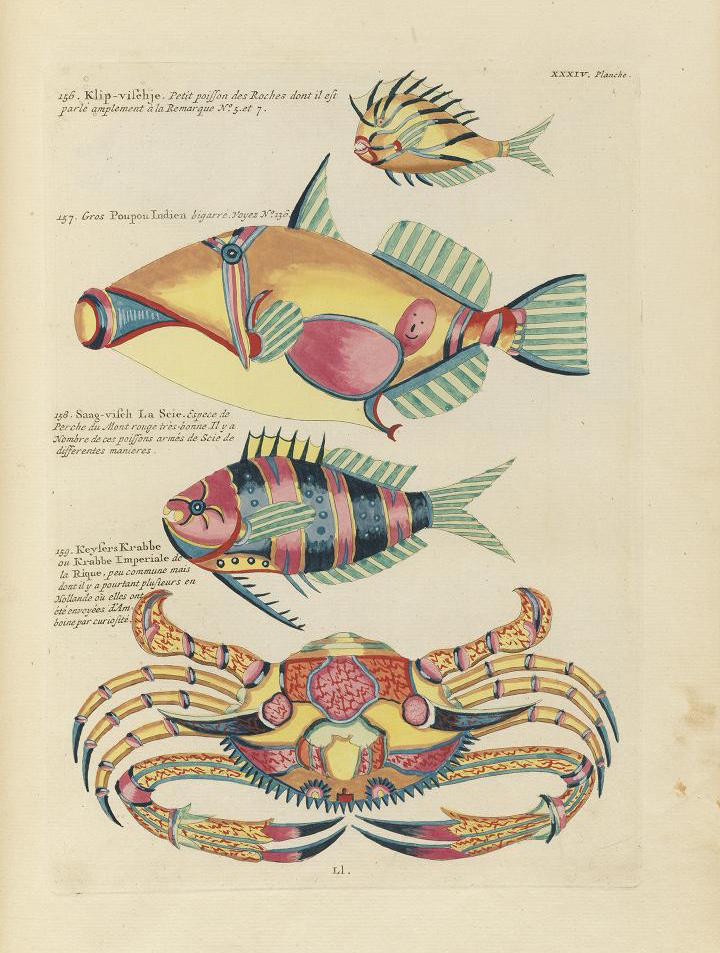

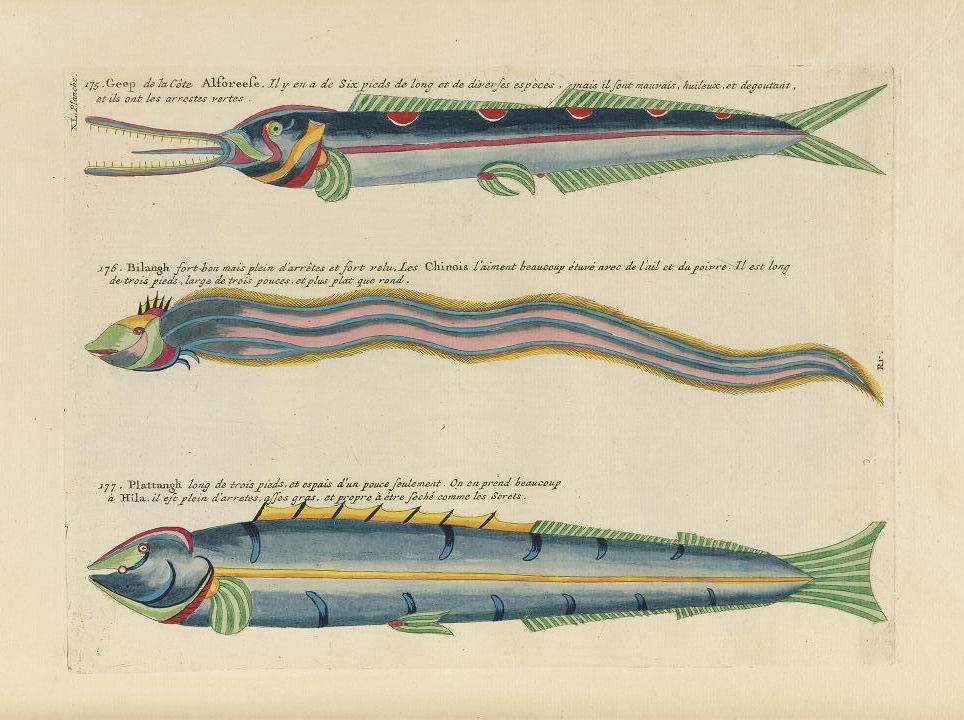

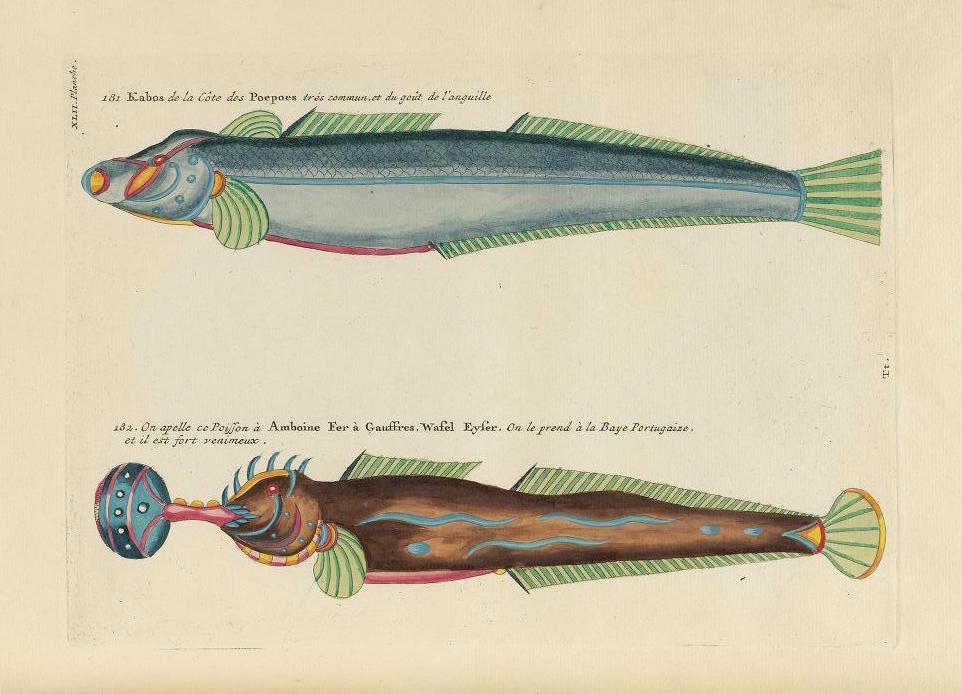

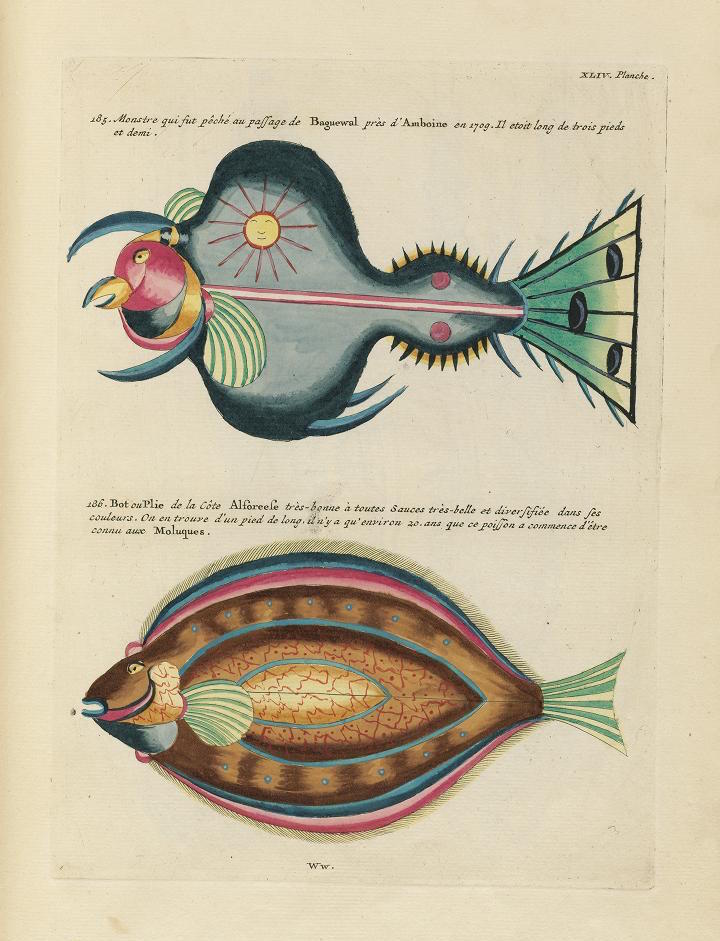

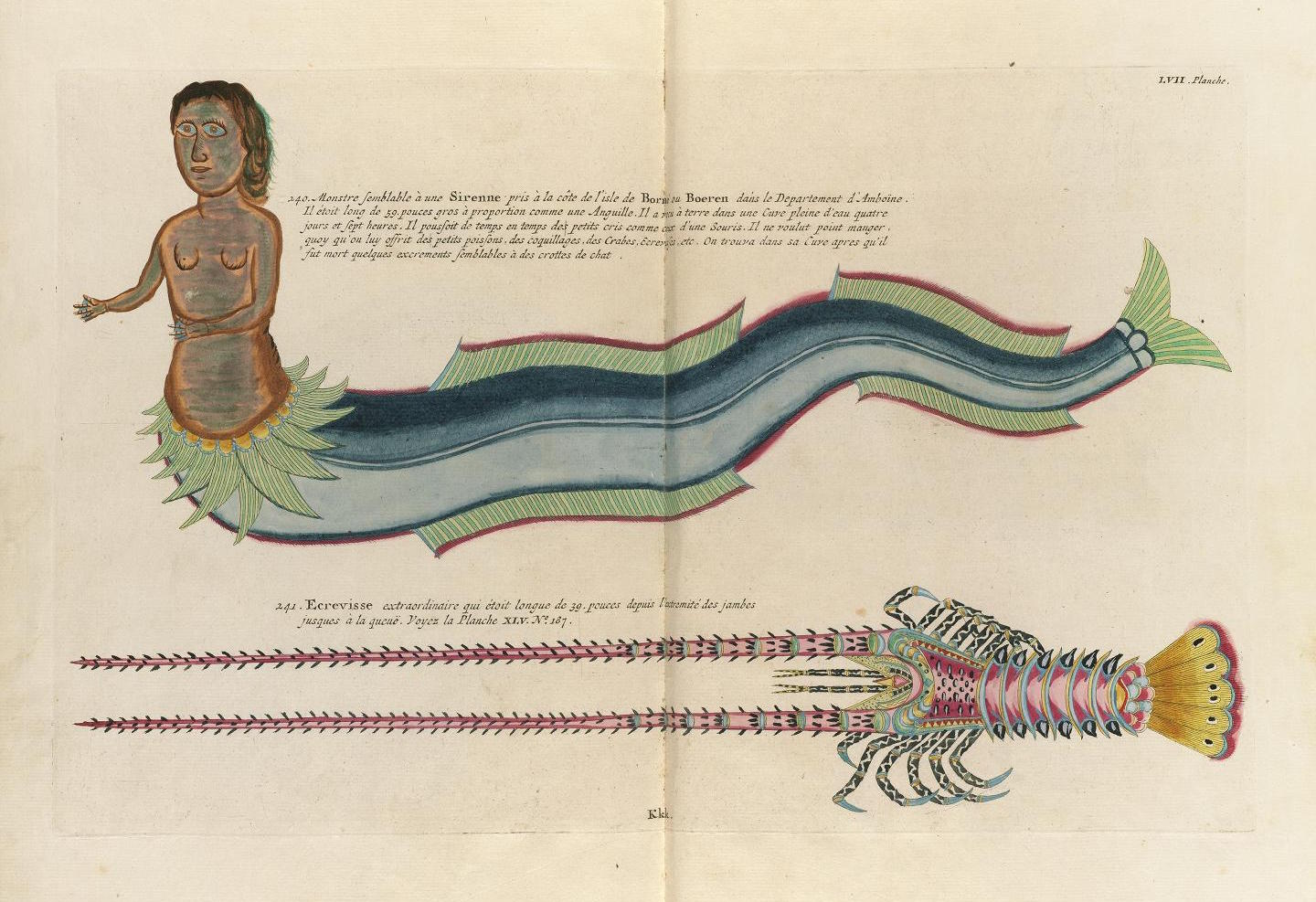

All in all, across the two volumes, the book contains 100 plates bearing 460 hand-coloured engravings — a total of 415 fishes, 41 crustaceans, two stick insects, a dugong and, in a final foldout, a solitary mermaid. The engravings were supposedly based on drawings from life by the artist Samuel Fallours (active 1703–20) which belonged to Baltazar Coyett, Governor of Ambon and Banda (1694–1706), and to Mr Van der Stael, Governor of the Molucca Islands. There is no main text as such, only that found in and amongst the images, which tends to be anecdotal, mainly focusing on recipes as opposed to science.

If the illustrations are breathtaking to us now, with all the hours of David Attenborough documentaries under our belts, one can only imagine the impact this would have had on a European audience of the eighteenth century, to which the exotic ocean life of the East would have been virtually unknown. Even for today’s most learned pescatologist, however, many of the illustrations might give some cause for surprise. Produced in two volumes, the images in the first part tend to be fairly realistic, but many in the second stray somewhat into the realms of fantasy, despite Renard’s ardent claims of authenticity. As Glasgow University Library explains, “many of the fish bear no similarity to any living creatures. Inaccuracies are found in the addition of small human faces, suns, moons and stars to the flanks of fishes and the carapaces of crabs. It would also seem that colours were applied in a rather arbitrary fashion.” It’s the expressive faces and outlandish colours, in particular, which give so many of the fish a cartoon-like quality, almost as though cast portraits from some sassy ocean-based animation.

In 2010, Taschen published Samuel Fallours: Tropical Fishes of the East Indies, which features Samuel Fallours’ original illustrations. See also a post about Renard’s book on the Biodiversity Heritage Library blog.

All in all, across the two volumes, the book contains 100 plates bearing 460 hand-coloured engravings — a total of 415 fishes, 41 crustaceans, two stick insects, a dugong and, in a final foldout, a solitary mermaid. The engravings were supposedly based on drawings from life by the artist Samuel Fallours (active 1703–20) which belonged to Baltazar Coyett, Governor of Ambon and Banda (1694–1706), and to Mr Van der Stael, Governor of the Molucca Islands. There is no main text as such, only that found in and amongst the images, which tends to be anecdotal, mainly focusing on recipes as opposed to science.

If the illustrations are breathtaking to us now, with all the hours of David Attenborough documentaries under our belts, one can only imagine the impact this would have had on a European audience of the eighteenth century, to which the exotic ocean life of the East would have been virtually unknown. Even for today’s most learned pescatologist, however, many of the illustrations might give some cause for surprise. Produced in two volumes, the images in the first part tend to be fairly realistic, but many in the second stray somewhat into the realms of fantasy, despite Renard’s ardent claims of authenticity. As Glasgow University Library explains, “many of the fish bear no similarity to any living creatures. Inaccuracies are found in the addition of small human faces, suns, moons and stars to the flanks of fishes and the carapaces of crabs. It would also seem that colours were applied in a rather arbitrary fashion.” It’s the expressive faces and outlandish colours, in particular, which give so many of the fish a cartoon-like quality, almost as though cast portraits from some sassy ocean-based animation.

In 2010, Taschen published Samuel Fallours: Tropical Fishes of the East Indies, which features Samuel Fallours’ original illustrations. See also a post about Renard’s book on the Biodiversity Heritage Library blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment